Epilog as prolog to start with.

Therefore, I will start with a description of two graves next to each other at the Jewish section of Innsbruck's Westfriedhof Cemetery. With the names of the Jewish men, Jakob Justman and Dawid Janaszewicz, both born in Poland and both died in the Spring year 1944 in Innsbruck, demand an explanation. It is a story about a long and difficult fate that must be connected to events in Europe during World War II. Graves in Innsbruck belong to two fathers who decided to save the lives of their daughters. One, Leokadia, a teenager at the beginning of the war who was just starting an adult life, and the other, Paulina, a little girl who was about to start second grade of primary school when the war started in September 1939, and her home city, Piotrków Trybunalski, was occupied by the Germans, and her mother Malka and little sister were killed. Later, individually, fathers with their daughters managed to escape the Piotrków Ghetto in 1942 with false identities.

What is remarkable is the fact that I have known about Leokadia and Paulina's fates for several years, but never connected them and their common fate during WWII. My parents met Leokadia in Boston in the 1970s because they had a common denominator, which was Dr. Janusz Korczak, and I met Paulina in 2020 at an elderly home in Stockholm when I was researching the fates of a group of Holocaust children who were liberated in Bergen-Belsen and came to Sweden through a UNRRA action.

Part of my father's war experiences, who escaped the Warsaw Ghetto. He registered as a volunteer Polish construction worker with the German employment agency and worked as such in a German building company at various locations in the occupied Soviet Union. My father's habitus resembles that of many Ukrainian men, and therefore, he chose the building company working in the Eastern areas of occupied Europe. In his German ID document, his name was Michal Wróblewski (not Wasserman) and his occupation was stated in German as "Professional murare". He was in a Polish group working for a German company in the Ukraine area, among others at the Kyiv Railway station. My father´s two stories from that time regarding his group transport between two work sites. (Harrassment of Jews sitting in the next wagon - shaving during the train trip to hide his strong dark facial hair).

A somewhat special sentence from a Swedish police interrogation that contains so many secrets: "There it was reported to the Gestapo that she and her sister and another girl were Jews, which is why they were arrested."

Part of my father's war experiences, who escaped the Warsaw Ghetto. He registered as a volunteer Polish construction worker with the German employment agency and worked as such in a German building company at various locations in the occupied Soviet Union. My father's habitus resembles that of many Ukrainian men, and therefore, he chose the building company working in the Eastern areas of occupied Europe. In his German ID document, his name was Michal Wróblewski (not Wasserman) and his occupation was stated in German as "Professional murare". He was in a Polish group working for a German company in the Ukraine area, among others at the Kyiv Railway station. My father´s two stories from that time regarding his group transport between two work sites. (Harrassment of Jews sitting in the next wagon - shaving during the train trip to hide his strong dark facial hair).

In another part of the Swedish police interrogation, Regina Rundbaken, born Litman, describes that she had with her one child, Paulina Janaszewicz, born in 1932: Her parents were the hairdresser David Shmul, born in Kus-Inskul, and his wife, who lived in Petrikow, Poland. Her mother had been killed in the German air force bombings in her hometown on 1 September 1939, and her father had died on 1 April 1944 in the Reichenau concentration camp. The child had also been in Reichenau for some time..., but had been imprisoned at the time.

In Landeck she stayed for 18 months and worked in a cotton mill. There it was reported to the Gestapo that she and her sister and another girl were Jews, which is why they were arrested. Mrs. Rundbaken and her sister were taken to a concentration camp in Innsbruck and then to prison in Innsbruck, where she was allowed to stay for 19 months. From there, Mrs. Rundbaken was taken to the concentration camp in Rawensbrück and then to Bergen Belsen, where she was allowed to stay until she was liberated by the British on April 15, 1945. (Swedish: I Landeck stannade hon 18 mânader och arbetade i bomullespinneri. Där blev det anmält till gestapo att hon och systern sant en annan flicka voro judar, varför de blevo arresterade. Fru Rundbaken och hennes syster blev förd till ett mindre läger i Innsbruck och därefter till fängelse i Innsbruck, där Hon fick stanna i 9 mânader. Därifran blev fru Rundbaken förd till koncentrationsläger i Ravensbrück och därefter till Bergen Belsen, där hon fick stanna till dess hon blev befriad av engelsmännen i april 1945).

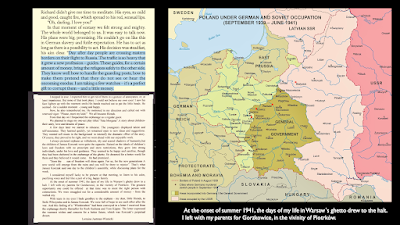

Necessary to study not only the Holocaust in Poland but also to understand the fate of the people described in Leokadia Justman's writings, as well as my own family's fate during that dark time. The photo on the right is of the city Brest-Litovsk, where Soviet and German commanders held a joint victory parade before German forces withdrew westward behind a new demarcation line, as shown on the map below, an addition to the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact. Some days before, German troops from the east and Soviet troops from the West surrounded the city of Lviv, which was defended by the Polish army.

The photos in the middle are of the Blitzkrieg and bombs falling on numerous Polish cities on the first days of the war. The first bombs fell on Piotrków Trybunalski on Friday, September 1, 1939, at around 10 a.m. On Saturday evening, September 2, after the tragic air raids, the exodus of civilians began. In all directions, the largest stream was, of course, towards the Soviet Union. The bombing of Warsaw starts on September 3rd. Thereafter, almost every day, this depends on the weather. On September 25, 1939, Warsaw experienced a bombing raid unseen in world history. From 7:00 a.m. until dusk, nearly 400 German bombers dropped bombs on the capital. Varsovians called this day Black Monday. Almost 630 tons of bombs fell on Warsaw. The planes flew in waves, dropping incendiary and demolition bombs. Around 200 fires broke out in the city. The total losses among the civilian population in September 1939 amounted to about 25,000. Many of the bombs fell in the areas of Warsaw that were highly populated by Jews. On September 17, 1939, the Red Army attacked Poland from the east along the entire Polish-Soviet border.

In September 1939, Poland was divided among Germany, Lithuania, the Soviet Union, and Slovakia. The territory under German administration was further divided into two areas: the Warthegau, which bordered Germany, and the Generalna Gubernia—General Government (GG), which comprised the rest of the country. While the Warthegau was annexed into Germany, the General Government was treated separately under the control of Hans Frank, one of Hitler’s chief advisors.

The war and the division of the land often led to the division of families. Division was often age-related.

Young tried to move east to the Soviet territories. It was both dangerous and expensive to cross the border, and in many cases, the Bug River had to be crossed.

Following the secret protocol to the non-aggression pact known later as the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, Germany and the Soviet Union partitioned Poland on September 29, 1939. The demarcation line ran along the Bug River. Leokadia Justman's big love, Ryszard, decided to move East, to the city of Bialystok, in the part of Poland occupied in September 1939 by the Soviet Union. Of course, all these types of trips were usually one-way, and it was uncertain when and if the family members would see each other again. Many young Jews tried to reach the city of Lviv, as it was a university city and had large Jewish population before WWII, about one-third of Lviv's population, numbering more than 200,000.

Łowicz

There was also a large movement of Jews between Warthegau, annexed into Germany itself, and the General Government. Part of this movement was forced by Germans who wanted Warthegau to be Jew-free and partly by single-family opinion, in which part of former Poland it would be easier to live. Of course, moving to another city was also costly, and only wealthy families with connections had such possibilities.

The first ghetto (Piotrków Trybunalski Ghetto) was set up on 8 October 1939, 5 weeks after the Germans entered the city. The Warsaw Ghetto, the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II, was established in November 1940. Ghettos isolated Jews by separating Jewish communities both from the Polish population as a whole and from neighboring Jewish communities. Piotrków Trybunalski Ghetto was an unfenced area, while the Warszawa Ghetto was surrounded by walls and heavily guarded. Heavily populated, food shortages, and diseases were typical for all the ghettos. Jews were forced to wear identifiers such as white armbands with a blue Star of David.

Szmalcownik ThreatsWord Szmalcownik comes from the German word schmalz, meaning "lard." In Polish slang, szmalec, later szmal, was used for "grease" or "money,". In other words, a szmalcownik was a person, sometimes gang, looking for extortion. The szmalcownik was a person who operated on the "Aryan side" of cities, where Jews were hiding after escaping ghettos. Their work was to identify Jews and blackmail them. Szmalcowniks were after Jews who were trying to pass as non-Jews and threatened to expose them to the German authorities, and also the Polish Policja granatowa, which often cooperated in this. The Szmalcowniks were operating everywhere as Jews on the run usually had all their belongings, valuables with them. Railway stations were one of the places they were present at, as well as on trains and tramways. They were also at all possible transfer places or institutions where escaping Jews were trying to get proper documents. They were also following groups of people volunteering at the Arbeitsamt for labor in Germany, as they knew the Jews were trying this method to escape annihilation. Some follow the group to later find out if there are Jews among the workers. A szmalcownik would threaten to denounce Jews to the Gestapo unless they were paid off with money or valuables. In some cases, after a Jewish victim was completely stripped of their assets, the szmalcownik would turn them in anyway to claim the reward offered by the Germans. These blackmailers not only robbed their victims but also created an extra atmosphere of terror and distrust outside the ghettos. Escaping Jews were often prepared for this type of robbery, having some valuables secretly hidden. Leokadia and her father, Litman sisters and Paulina Janaszewicz and her father were surely threatened by Szmalcowniks.

The photos in the middle are of the Blitzkrieg and bombs falling on numerous Polish cities on the first days of the war. The first bombs fell on Piotrków Trybunalski on Friday, September 1, 1939, at around 10 a.m. On Saturday evening, September 2, after the tragic air raids, the exodus of civilians began. In all directions, the largest stream was, of course, towards the Soviet Union. The bombing of Warsaw starts on September 3rd. Thereafter, almost every day, this depends on the weather. On September 25, 1939, Warsaw experienced a bombing raid unseen in world history. From 7:00 a.m. until dusk, nearly 400 German bombers dropped bombs on the capital. Varsovians called this day Black Monday. Almost 630 tons of bombs fell on Warsaw. The planes flew in waves, dropping incendiary and demolition bombs. Around 200 fires broke out in the city. The total losses among the civilian population in September 1939 amounted to about 25,000. Many of the bombs fell in the areas of Warsaw that were highly populated by Jews. On September 17, 1939, the Red Army attacked Poland from the east along the entire Polish-Soviet border.

In September 1939, Poland was divided among Germany, Lithuania, the Soviet Union, and Slovakia. The territory under German administration was further divided into two areas: the Warthegau, which bordered Germany, and the Generalna Gubernia—General Government (GG), which comprised the rest of the country. While the Warthegau was annexed into Germany, the General Government was treated separately under the control of Hans Frank, one of Hitler’s chief advisors.

The war and the division of the land often led to the division of families. Division was often age-related.

Young tried to move east to the Soviet territories. It was both dangerous and expensive to cross the border, and in many cases, the Bug River had to be crossed.

Following the secret protocol to the non-aggression pact known later as the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, Germany and the Soviet Union partitioned Poland on September 29, 1939. The demarcation line ran along the Bug River. Leokadia Justman's big love, Ryszard, decided to move East, to the city of Bialystok, in the part of Poland occupied in September 1939 by the Soviet Union. Of course, all these types of trips were usually one-way, and it was uncertain when and if the family members would see each other again. Many young Jews tried to reach the city of Lviv, as it was a university city and had large Jewish population before WWII, about one-third of Lviv's population, numbering more than 200,000.

Łowicz

There was also a large movement of Jews between Warthegau, annexed into Germany itself, and the General Government. Part of this movement was forced by Germans who wanted Warthegau to be Jew-free and partly by single-family opinion, in which part of former Poland it would be easier to live. Of course, moving to another city was also costly, and only wealthy families with connections had such possibilities.

The first ghetto (Piotrków Trybunalski Ghetto) was set up on 8 October 1939, 5 weeks after the Germans entered the city. The Warsaw Ghetto, the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II, was established in November 1940. Ghettos isolated Jews by separating Jewish communities both from the Polish population as a whole and from neighboring Jewish communities. Piotrków Trybunalski Ghetto was an unfenced area, while the Warszawa Ghetto was surrounded by walls and heavily guarded. Heavily populated, food shortages, and diseases were typical for all the ghettos. Jews were forced to wear identifiers such as white armbands with a blue Star of David.

Szmalcownik Threats

Every transfer, thus exposing to the Polish-Christian people and Germans outside the ghettos, was therefore very risky. Polish-Christians volunteering at the Arbeitsamt for labor in Germany were a direct threat too. Not only at the local Arbeitsamt offices but also later during numerous transfers, thus traveling to the desired work and also at the final destination in Germany. Workers chosen by the Arbeitsamt often traveled in the group by train and had to re-register at transfer points before reaching the final destination in Germany. Re-registration was often connected with a common bath and a new interrogation. It is well documented.

Warszawa Ghetto

Why move into the ghetto? This was a question that bothered me for years. Why did my parents move from Lviv back to the Warsaw ghetto? They traveled almost 500 km. The Justman family traveled in the same way for almost 100 km. They do not step out of the train. From the train station in Warszawa, they went directly to the ghetto gate. Inside the ghetto, they felt relatively secure. They could no longer be denounced as Jews. But the ghettos were nothing but a trap with possibilities to survive diminishing every day. Many Jews believed in a "working camp solution" until the liberation - Deportation to the East. However, throughout Europe, a few thousand Jews also survived in hiding or with false papers posing as non-Jews. Thousands of Jews who escaped the ghettos and hid in Eastern European forests survived the Holocaust. A small group of Jewish children survived in convents after the conversion of many of these children to Christianity.

The most important experience for Leokadia was meeting Janusz Korczak, who allowed her to work with the orphanage children. The main project was to put Leokadias' play "Fatamorgana" on stage. Leokadia described the meeting with Korczak and her own experiences with children in the Preface to her book The Saga of Janusz Korczak. She also explained there that after she left the Warszawa Ghetto, Korczak sent her Jewish New Year and Yom Kippur cards to Gorzkowice. She was, however, never mentioning that she was sending to Korczak proofs of her poetry, asking for his opinion.

I love her unique description of the Friday meeting* at the Orphanage:

"Soon the -. sun of freedom will shine again. For us, for the new generations, Anew world will emerge from the ruins and you will be there to rejoice". That's whatJanusz Korczak said one day to the children's assembly while discussing plans for theweek. I considered myself lucky to be present at that meeting, to listen to his calm,pacifying voice and feel like a part of a big, happy family.At the onset of summer 1941, the days of my life in Warsaw's ghetto drew to ahalt. I left with my parents for Gorzkowice, in the vicinity of Piotrkow.

Theatre and writing were common interests for young Leokadia (born 1922) and Janusz Korczak. When Korczak was the same age, he started to write his first plays. In March 1898, one of his two plays submitted to a literary contest announced by Ignacy Jan Paderewski received a special mention (published in a newspaper) in a contest for the play entitled Którędy? - Which Way? (Quo Vadis). Korczak's interest in writing theatre plays resulted finally in a play that was put on the stage in Ateneum Theatre in Warszawa. The play, "Senat szaleńców, humoreska ponura" (Madmen's Senate, premièred at the Ateneum Theatre in Warsaw, 1931 was not a success. Korczak continued writing small plays for the children in his newspaper Maly Przeglad. In Korczak's orphanage, the theatre group, before and during the war, performed plays at other orphanages and at "Kitchens".

It was a great episode for me when I, just hours before leaving for the Innsbruck meeting, found by accident a copy of a letter from Korczak to Leokadia.

|

| It was a great episode for me when I, just hours before leaving for the Innsbruck meeting, found by accident a copy of a letter from Korczak to Leokadia. |

Justman wrote in her novel:

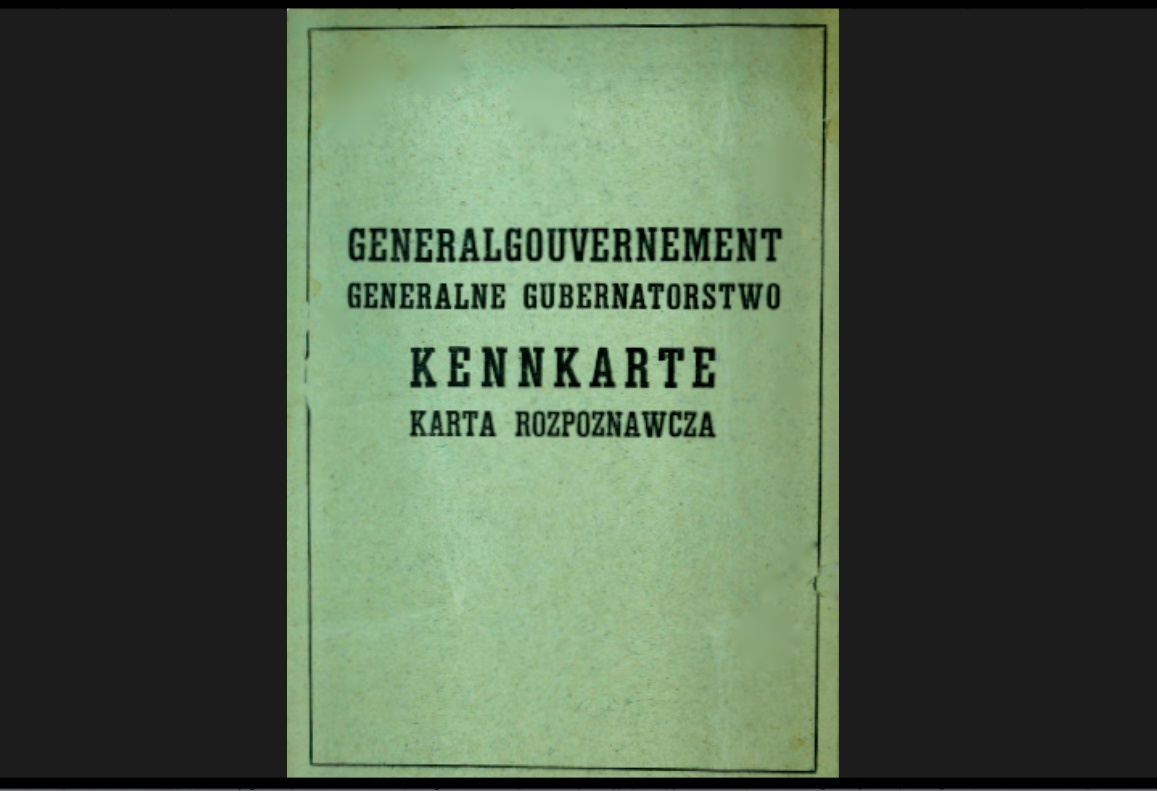

Our decision to escape was sealed now. My father made connections while working outside, and our new identification papers were already finished. Our assumed names had a clear Polish sound, and the stated religion was Roman Catholic, the reigning religion of the Polish population.

Identification papers she meant above were Kennkarte. As Kennkarte could be checked, the real person's identity details should be included. Also, a photograph with an Aryan look should be taken. The new identity had to be carefully learned and rehearsed. An Aryan Kennkarte was required to apply for work in Germany - Zivilarbeiter. The German authorities tried to relieve the labor shortage in the Third Reich by starting with the voluntary recruitment of foreign workers. German military campaigns and the conquests of neighboring European countries were accompanied by the enlistment of the civilian population as a workforce. The very first work-recruitment agencies, Arbeitsamt, were planned before WWII started and were set up by Germans in major Polish cities. The first Arbeitsamt was established on September 3, 1939, in Rybnik, and by the end of that September, its number had increased to seventy. The voluntary recruitment of foreign workers was not enough to compensate for the former German workers, now in the army. Arbeitsamt was also involved in supplying forced labor workers.

Danger for the Jews using false identities.

The biggest danger for the Jews using false identities was, besides the Germans, also the Polish people. The very first could be to be recognized in the home city when leaving the ghetto. Therefore, most of the Jews trying to mix with the Polish workers used to get on trains in neighboring cities. The next danger was at the gathering point for the workers before leaving for the final destination. Here, again, they could meet Polish neighbors. The denunciation of Jews was possible and probably most frequent at work or in the cities where they worked.

Historian Professor Emanuel Ringelblum (to be checked if it was his notes) wrote in his notes from the Warsaw Ghetto about Jews volunteering at the Arbeitsamt for labor in Germany. Of course, it was possible only for those with forged Kennkartes (Kentkartes) and the courage to take such a dangerous alternative. Before receiving Arbeitsamt documents, in the case of a complete medical examination demanded by the Germans, a paid-for Pole would take the place of a Jew.

Prior and during the Actions in the ghettos.

The final stage of a ghetto existence was its "liquidation,". It involved rounding up all remaining Jewish inhabitants, deporting them to death or concentration camps. The German term "Aktion" ("action") refers to large-scale, brutal round-up operations of Jewish residents and mass deportation. The Germans often used euphemisms like "resettlement to the East" to mask the true purpose of the roundups and deportations.

Before the Actions in the ghettos, the General Government started during the Summer of 1942, numerous Jewish families had gone through the experience of trying to hide their children, mainly girls, in Catholic families. Paying a lot of money for that. However, several hidden children were expelled from the ward families back to ghettos. Children were also hidden in cloisters.

It is also important to mention that poor families or those without contact with the Judenrat had difficulties being among the workers at the factories like Hortensja, Kara, and Bugaj, owned or run by the Germans. When, in early March 1942, the German administration in Piotrków ordered the ghetto to be closed by April 1, 1942, numerous Jews of the Piotrków ghetto tried to be admitted to the factories.

Rumors were spread that only 3,000 "productive Jews" would remain for work at the factories owned by the Germans. At this time, thousands of Jews were brought into the ghetto from the nearby towns and villages, such as Sulejow, Srocko, Prywatne, Wolborz, Gorzkowice, and others. These actions increased the ghetto population to some 25,000 or even more. The tension in the ghetto increased after the news about the Great Action in the Warsaw Ghetto. It reached its climax on October 13, 1942, when the horrifying news spread that the Aktion in the Piotrków Trybunalski ghetto was scheduled to begin on the following day.

Rumors about deportations of the Piotrków Jews to Treblinka reached Piotrków in late September. Paulina's father already planned to escape and arranged forged documents for Paulina, himself, and Litman's sisters. On October 13th, Paulina and Litman's sisters leave the ghetto and travel to Austria. They were pretending to be Polish workers and had to be first to be examined for the job at a transit point in the city of Częstochowa. Paulina's father, who could be more easily detected as a Jew, travels later, alone, and rejoins Paulina and the Litman sisters later in Austria, in Landeck. It is possible that Miriam Fuks also left Piotrków Ghetto and travelled with them. Anyhow, the entire group succeeded with forged papers to reach Landeck in Tyrol. All of them got work at the local weaving mill.

The deportations started on October 14 and lasted until October 21, 1942. During this main wave of deportations, most of the ghetto's population was deported. At that time, the ghetto held approximately 28,000 people. Before deportation, the Germans conducted a selection at the assembly point in Piotrków. Jews able to work, holders of so-called labor cards, were temporarily left in the city. All remaining people, including the sick, the elderly, women, and children, were deported to the extermination camp in Treblinka. Approximately 3,000 Jews who remained in Piotrków were working as forced labor for the occupiers. They were gradually deported to labor camps such as Skarżysko-Kamienna and later, at the end of 1944, to the concentration camps Ravensbrück and Buchenwald.

Xtra

From the assembly point in Piotrków, Jews were led to cattle cars close to the railway station. Thereafter transported in overcrowded cattle cars to the extermination camp Treblinka, where they were murdered in gas chambers.

Dangerous life in Landeck.

The main danger for the Justman and Janaszewicz families was actually Polish workers at their work at weaving mill and also other "Polish workers" in the city. No one could be trusted. After some months in Landeck, Paulina's father, Janaszewicz, wanted to find total security for his daughter and Rywka-Regina Rundbaken (born Litman), who became Paulina's stepmother. They, together with Reginas sister were trying to make a well-planned "Sunday excursion" to the Swiss border. Of course, they were planning to escape the German rulled Austria. However, they were all arrested, sent to Innsbruck, and charged in the Court of Justice. At the court, the prosecutor believed (actually wanted to believe) their fabricated story about a tourist trip into the border to see the Swiss Alps and sent them back to Landeck and their previous jobs at the weaving mill.

My feeling is that numerous of the Polish workers that were working in Landeck knew that they were Jewish but they were just letting them be. The same situation was when the groups of voluntary foreign workers att recruitment and transfer points of - interactions - Betraying Jews as an act of antisemitism, hate, simple play or just part of a concurens fot the jobs.

Later, they were simply denounced by other workers at the weaving mill and arrested by the Gestapo on March 13, 1944. They were accused of being Jews and posing as Christian-Polish foreign workers. Paulina and Litman's sisters were sent to Innsbruck prison, while Janaszewicz was sent to KZ Reichenau.

Later, they were simply denounced by other workers at the weaving mill and arrested by the Gestapo on March 13, 1944. They were accused of being Jews and posing as Christian-Polish foreign workers. Paulina and Litman's sisters were sent to Innsbruck prison, while Janaszewicz was sent to KZ Reichenau.

When it comes to Leokadia, it is quite clear that her mother sacrificed herself and took a place in a freight car to the Treblinka death camp in the hope that Leokadia would survive. For the Litman sisters who took care of little Paulinka, there was a similar challenge. There was also another problem that had to do with appearance, the Aryan appearance that all Jews tried to imitate. However, it wasn't just about appearance. Equally important was a way of behaving, speaking, and, not least, having your own story to stick to. Leokadia, in her book, narrates the sisters Litman and Paulina in the prison in Innsbruck. She describes the strong contrast in appearance between the sisters and Paulinka, where the sisters are blonde, have blue eyes, and hold their heads high. Paulinka, on the other hand, looks clearly Jewish with darker skin, dark hai,r and eyes. My mother and aunt had exactly the same situation with the third sister's child, a four-year-old boy who was also circumcised. The sisters were blonde, had blue eyes, spoke perfect Polish, while the boy had dark eyes and did not fit their look. The boy's father decided not to follow the family, not to escape the ghetto, as he knew he had a Jewish look and that this would diminish the chances of the rest surviving. In the same way, Paulina's father, do travel to Austria with later and alone, and meets Paulina and the Litman sisters first later in Austria, in Landeck.

I have to point out here my mother, who told me that her determination to save the child of her late sister was the main force to fight for her own survival. As I mentioned, besides having the right documents with false identities, Jews hiding among Arians needed the new, fabricated story of their lives and also meticulously stick to it. No single change in their newly fabricated life story could be changed or forgotten, of course, not their new names. My mother, when liberated, said that it was so wonderful to finally stop playing the theatre. However, she and her sister never fully returned to their prewar identity and had different names for their parents, place, and date of birth.

Epilog as epilog to end with, or Panna Leokadia meets Pan Misza.

As I mentioned above, theatre and writing were common interests for young Leokadia and Dr. Janusz Korczak (Pan Doktor). Leokadia was called by the Orphanage children for Panna Leokadia (Miss Leokadia). She was active there in the production of her own plays, starting some months after the Warsaw Ghetto was created at the end of 1940. Pan Misza (Mr. Misza), my father, worked at Korczak´s Orphanage from 1931 until the last day of its existence, August 5th, 1942. He was present at the so later called "The last play in the Warsaw Ghetto". It was staged at Janusz Korczak's orphanage, now located at 16 Sienna Street in the Southern border of the Little Ghetto. The play was The Post Office by Nobel Prize winner Rabindranath Tagore. The performance took place on July 18, 1942, only four days before the mass deportation, 17 days before Korczak, teachers, and 239 children were sent on August 5th to the Treblinka extermination camp. Play, The Post Office, is about Amal, a dying boy awaiting a letter from the king, resonated deeply with the children who identified themself with the protagonist. Actually, not only did the orphanage children identify with Amal's fate, but the entire public, including guests invited by Korczak, among them a friend of Korczak's and the Judenrat leader, Adam Czerniakow and Icchack Cukierman that in the Spring 1943 became deputy commander of the Ghetto Uprise. My mother, who attended both the last Hanukkah celebration at the Orphanage on Sienna Street in December 1941 and the last theatrical performance of the play "The Post Office" on July 18, 1942, recalled: "The very fact that Korczak, in such tragic conditions, was able to care for and persistently strive not only for his daily bread, but also for cultural entertainment, for an almost normal lifestyle in the boarding school, was admirable.".

The play "The Post Office" was a specific lesson on dying, and there was a long, complete silence in the audience after the play ended. My father and three of the older boys, former pupils, were the only ones who survived the deportation on that day as they left the Orphanage very, very early for the jobs Korczak had been able to arrange for them at the German railway depot on the other side of the wall. My father and Leokadia (now Lorraine) actually met in Boston at the beginning of the 80s in a private meeting organized by Gina Shrut (Gina Tabaczyńska), another young girl from the Warsaw Ghetto who survived the Holocaust. I can only guess what they were talking about.

To add: During the German bombing of Piotrków Trybunalski area in September 1939, one of the bombs hit Dawid Janaszewicz's summer house and killed his wife, Malka, and the youngest daughter, Sara-Ita. Janaszewicz and his elder daughter, Paulina, survive.

|

| Office of voluntary recruitment of Polish workers for work in Germany. |

|

|

..png)