|

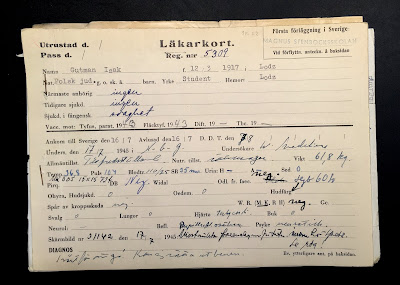

Vita bussar med blåa inresekort och Vita skepp med de bruna. Weisz Eva kom med de Vita bussarna och Weinberger Rozi med de Vita fartygen. Båda dog strax efter att ha kommit till Sverige för vård.

|

| Victoria Martinez writes in an article in The Local about Holocaust survivors buried in Stockholm |

Victoria Martinez wrote an article How Stockholm is restoring dignity to the neglected graves of 100 Holocaust victims. Afterwards, I was interviewed by Ellen Gruber

The project is spearheaded by Roman Wroblewski, the Polish-born son of Holocaust survivors who fled to Sweden in 1967. Wroblewski, an emeritus medical school professor, also conceived the main Holocaust memorial in Stockholm, dedicated at the city’s synagogue in 1998. That memorial lists around 8,500 names of Holocaust victims who were relatives of survivors who settled in Sweden after the war.

On the new memorial project, Wroblewski is working with city authorities and with the Stockholm Jewish community.

He presented a detailed plan for the project to city authorities at the end of 2018, and also contacted the director of the city museum earlier in the fall. Funds are now being sought for what he told JHE would be an approximately €145,000 undertaking.

Almost all of the burials in the plot are of women and girls who had been among survivors who were found at or brought to Bergen-Belsen after its liberation by British forces in April 1945. (Tens of thousands of prisoners were found starving or suffering from typhus and other diseases when Bergen-Belsen was liberated — Anne Frank had succumbed not long before liberation.)

Victoria Martinez writes in an article in The Local that the people buried in Stockholm are believed to have been brought over on one ship:

All of the victims buried at the site share several similarities, starting with the fact that most of them had been transferred from Auschwitz to Bergen-Belsen, a concentration camp in Northern Germany, where they were eventually liberated on April 15th, 1945.Though they managed to survive to liberation, they were seriously ill when they boarded the S/S Kastelholm, one of the Swedish Red Cross’ “White Ships” that transported survivors from Germany to Sweden, in the summer of 1945. In two crossings, the ship carried 400 survivors from Lübeck, Germany, to Stockholm’s Frihamnen port, including all of those buried in the Northern Cemetery.

|

About the White Ships in Swedish and Summary in English. In Swedish De vita skeppen — en svensk humanitär operation 1945 by Sune Birke, five “White Ships” were in operation and brought more than 9,200 Holocaust survivors from Germany to Sweden.

|

Links to the project in English

or

https://jewish-heritage-europe.eu/2019/01/31/sweden-restoring-the-graves/?fbclid=IwAR2eSdLqSMgohB53R12IAZfjRj3tFsrl-JHcJ1sgWhxe6LRLajGg0YEDxdk

https://sjohistoriskasamfundet.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/fn58-lag.pdf

De vita skeppen — en svensk humanitär operation 1945 by Sune Birke, five “White Ships” were in operation and brought more than 9,200 Holocaust survivors from Germany to Sweden. Birke wrote that Bergen-Belsen had been chosen by British authorities “as a terminal for collecting [survivors] from all of the British occupation zone.” (You can read an English summary of this article below or by clicking HERE and scrolling down to page 94).

English summary of Sune Birke: The White Ships

Prologue

In the summer of 1945 Swedish ships carried out a remarkable humanitarian and maritime mission when more than 9 000 ex-concentration camp prisoners ("displaced persons") were taken over the Baltic from Germany to Sweden in one month for rehabilitation. This mission has passed through history fairly unnoticed, although it contains some very interesting details relating to the planning and organizing of the mission, its reception by British forces in Luebeck, and escort by German minesweepers as well as other items. My main sources for this paper have been the acts of the Royal Naval Board of Logistics and of the Naval Staff; the log and the final report from the hospital ship H Sw MS Prins Carl and the final report from the Swedish Red Cross detachment in Luebeck. All of these acts can be easily found in the Swedish War Archive or State Archive. I have not considered it necessary for my purpose to go through the acts of the civilian ship companies concerned, nor the logs of the participating merchant ships. In my opinion, the material I have used is sufficient to provide an overall view of how the mission was decided, planned, and carried out. The decision The formal decision to undertake this mission was taken by the King in State Council on the l st of June 1945. Before that, on May 30th, a telegram from the UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration) to the Swedish Committee for International Charity stated that the UNRRA had decided to accept the "helpful offer of your government" to welcome some 10 000 displaced persons to Sweden. Unfortunately, however, the telegram tells us nothing of when and how this offer was made. In any event, the telegram was submitted by the Committee to the Social ministry on May 31st and became the trigger for the formal decision. This very quick process seems to tell us, that the mission, in fact, had already been prepared for same time before the telegram arrived. The decision, then, stated that Sweden was to receive for rehabilitation, at most l0 000 displaced persons who were under repatriation by the UNRAA. The Royal Board of Civilian Defence was given the task of organizing the transport of those persons from Germany to Sweden, and the Board of Naval Logistics was to provide the ships. 95 The ships selected for the mission were: HMS Prins Carl, a hospital ship, launched in 1931 as the S/S Munin, a freight and passenger steamer, which was taken over by the Navy in 1939 and recommissioned for the new task; S/S Kastelholm, a passenger steamer designed mainly for the Baltic waters, launched in 1929; M/S Kronprinsessan Ingrid, a car- and passenger ship, launched in 1936 to cross the route over the Skagerak between Sweden and Denmark; M/S Karskär and Rönns kär, launched in 1943 for use in the Baltic and the North Sea. Preparations The formalities concerned with the renting of the civilian ships went very smoothly, apparently having been prepared in advance. Now the ships had to be modified and rebuilt for their new task. Obviously, the need for this was greatest as regards the two cargo ships, which had to be fitted out with beds for some 260 persons in their cargo rooms. All the work was carried out in Swedish naval or civilian dockyards before the 20th of June. At the same time, a Swedish Red Cross detachment was organized in Luebeck, manned by Swedish, German and British personnel. The purpose of the detachment was to receive an estimated 2 000 displaced persons a week. They were to arrive by train from the infamous concentration camp Bergen-Belsen, which was chosen by the British authorities as a terminal for co11ecting them from all over the British occupation zone. From the detachment, they were to be sent down to the ships. Thus you could say that the commander of the Luebeck detachment actually regulated the timetables of the ships. The first voyage to Luebeck The ships were assembled in Trelleborg on June 22nd, and shortly after they sailed for Luebeck. The distance was some 150 nautical miles, and the time for the voyage 13 - 14 hours. It is interesting to note that the Swedish ships were escorted over the Baltic by German, ex-Kriegsmarine minesweepers, still sailing with their original crews hut flying the allied control flag. In Luebeck, which had been little damaged by the war, there was a small Royal Navy presence. The overall command, however, was executed by the British 21st Army Group, which seems to have had a rather difficult job in maintaining law and order in the city. The streets were crowded with unemployed Germans as well as liberated foreign slave laborers waiting for repatriation and on the first night the British shot seven Poles who were caught plundering. As a result, obviously, of this rather tense situation, the British did not allow the Swedish crews to go ashore on leave, a decision that was very unpopular and that was later rescinded. While the Swedish ships were being fitted out with German devices against caustic mines, the first patients arrived at the Swedish Luebeck detachment. The Swedish conditions were, that the patients selected, should be medically fit for transportation to Sweden, should have a good chance of being rehabilitated, and should not suffer from any epidemical disease. It seems that the British authorities who delivered the patients did not observe these conditions; many of the patients were in very bad condition, suffering from severe malnutrition and tuberculosis, and, in fact, a few of them did not survive the voyage. The patients were taken care of in the detachment and from there sent forward to the ships. During the 27th and 28th of June, Karskär, Rönnskär, Kastelholm, and Prins Carl took aboard some 200 patients each, while the Kronprinsessan Ingrid took a few more than 400. Those patients were taken back to Sweden and, depending on their condition, sent to various Swedish hospitals. The mission goes on In short, the command and control structure of the mission might be described as follows: • The overall command and responsibility rested on the Board of Civilian Defence, assisted in strictly medical matters by the Board of Medical administration; • The command in place in Luebeck was held by the commandant of the Luebeck detachment, who supervised the arrival of patients from Belsen and their departure by ship to Sweden; • The Naval Staff had the task of following the movements of the ships at sea, maintaining radio communication and transmitting messages and logistical requests. lt also had to take decisions relating to naval matters (eg whether the ships should be escorted by minesweepers or not). • The command of the ships at sea rested on each individual captain. More often than not, the ships seem to have maneuvered rather independently of each other. The subsequent voyages were rather like the first one, with some exceptions. For instance, the demand for an escort by minesweepers on the voyage was dropped. After demands from the Naval Staff to the UK Embassy in Stockholm, the 21st Army Group eventually withdraw the prohibition against shore leave. The time in harbor, both in Luebeck and in Sweden, was shortened, due to the fact that experience had been gained and also, it seems because the patients were in a better medical condition. Nothing extraordinary seems to have happened during the voyages except that some patients died, as I mentioned earlier. For instance, the Prins Carl had 7 casualties in all. To summarise, the voyages were carried out in the following manner: Ship Number of voyages, an Average number of patients each voyage HSwMS Prins Carl 4 150-200 M/S Kronprinsessan Ingrid 8 400-450 S/S Kastelholm 5 200-235 M/S Karskär lO 240 M/S Rönnskär 9 240 Beginning Jul y 17th, the Prins Carl also made two voyages from Malmö to Gotland with patients afflicted by tuberculosis who were taken to a Swedish military hospital for treatment. End of the mission From the middle of July, the commandant of the Luebeck detachment had frequent talks with the British about when to end the mission. The goal, l0 000 patients, was el o se at hand, and the British seemed to be having some trouble finding more patients. Thus, S/S Kastelholm made the last voyage on July 25th. The civilian ships were restored to their previous condition and returned to their owners in the beginning of August. The result, In my opinion, the commandant of the Luebeck detachment gives the most accurate estimation of the number of patients evacuated from Germany in his final report According to his numbering, from June 23rd to July 25th, 1945, 9 373 patients were received by the detachment and 9 273 sent over the Baltic to Sweden with the White Ships. The majority of them were of Central or Eastern European origin. More than half of them were Poles, and the main part comprised of women.